Chance, Chaos and Coincidence

Introduction

Chance, Chaos, Coincidence. The mainstays of many a mediocre movie (apologies for the annoying alliterations), these concepts have long been consigned to cameo appearances that clean up particularly knotty storyline issues unresolvable by any other means. Consequently, it is no surprise that they have long yearned -- even longer than Kobe Bryant -- to be centerpieces in a movie all their own. These yearnings have been successfully fulfilled in three recent, highly innovative, yet dramatically different films. "Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels" revels in chaos and coincidence, "Run Lola Run" is troubled by them, while "Three Colors: Red" is a meditation upon them.

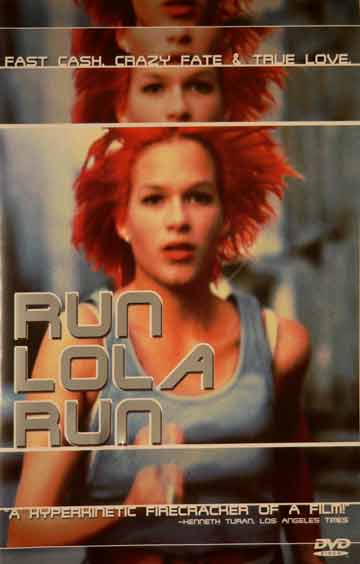

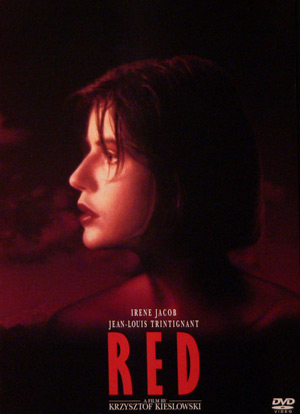

All three films (coincidentally?) turn out to be an auditory and visual delight, although in vastly different ways. The visuals and music in "Lock, Stock..." are characterized by playfulness. We are treated to such bizarre sights as a bottom-up view of vegetables being dropped into a pan of boiling water; music is used for subtle parody, such as with the use of the "Zorba the Greek" theme to herald every appearance of a Greek character. "Run Lola Run" is one long music video, combining a wide variety of styles, including freeze frames, split screens and even a dash of animation; the techno soundtrack proves an ideal foil and, what's more, is composed entirely by the director Tom Tykwer, with vocals from star Franka Potente! "Red" is distinguished by sedate, graceful compositions with elegant colors and a variety of visual motifs; Zbigniew Preisner's classical strains complement the film's mood perfectly.

All in all, three different films in three different languages emphasizing three different facets of the same theme.

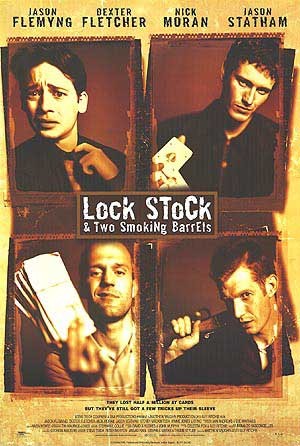

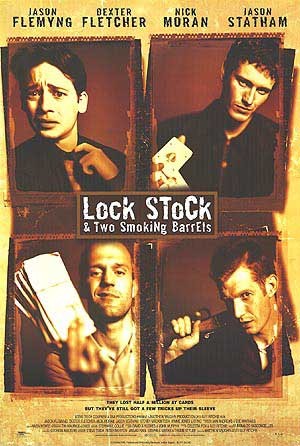

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels

The deftly titled, sublimely

plotted, cockney-crime-comedy

debut of director Guy Ritchie, "Lock,

Stock and Two Smoking Barrels"

is looking increasingly likely to be the high point of a directorial

career which has since stumbled through the minor missteps of a

competent, but inferior, imitation (Snatch)

before walking off the cliff with the unseen-by-me but allegedly

atrocious, made-for-Madonna stinker "Swept

Away".

Perhaps someone

ought to remind Guy Ritchie not to mix business with pleasure -- at

least, when the pleasure involves being married to a

superstar-singer

who can't act.

"Lock,

Stock...", though, is a

fortuitous coming together of hard-edged, but delightfully urbane and

witty dialogue (with liberal doses of Cockney slang), a story filled to

the brim with wildly quirky, one-of-a-kind characters, and a

convoluted plot in which the various threads criss-cross themselves at

such dizzying speed that it feels like a major miracle when the dust

settles and the complications dissolve in a logical resolution.

If

there is a God in the world

of "Lock, Stock...", then he is surely blessed (?) with a cosmic sense

of humor. Nearly every character's fortunes swing

wildly from one extreme to another, turning, it appears, on

the wildest of coincidences. It all starts out with our four heroes

managing to land themselves 500,000 pounds in debt, thanks to a poker

hand gone bad. Ironically, the outcome of this game of chance is the

one vagary of fate in the entire movie for which Lady Luck is least to

blame! To give away the rest of the story would be to spoil the fun.

Suffice it to say that the machinations of God deftly intermingle the

fates of a whole host of characters with a series of chance meetings.

Fortunes turn this way and that with each such accident, and the plot

keeps thickening further and further, its complexity rising in a

crescendo for what seems an unsustainable length of time, before

resolving itself on a final note of sly delicacy.

Normally,

a story involving

coincidences sets off alarm bells, for it often heralds intellectual

laziness -- a desire to achieve a predetermined resolution (usually,

"the Hollywood ending") without the willingness to establish a

plausible sequence of events leading up to it. The

result is the

coincidence as deus

ex machina -- God

playing with loaded dice to rescue the hopelessly tangled, insoluble

mess

of a story from the clutches of its clueless author. So, what

distinguishes "Lock, Stock.." from the mediocre ranks of the

coincidence-as-crutch movies? The distinction lies both in

the film's intent and in its execution.

While the deus

ex machina exists to resolve

complexity, this film uses coincidence as much to build

complexity as it does to resolve it. There are chance

occurrences aplenty, but not one of them has predictable consequences;

as a result, not only are we kept on our toes in anticipation of what

happens next, but we also begin to realize that the coincidences are

not the filmmakers' tool to manipulate the story, but a serious

obstacle to their engineering of a predetermined conclusion.

Thus, when the film eventually manages to land on its feet, we are left

with renewed admiration for the difficult juggling act involved in

finding an elegant way out of the maze of complications.

Critics who complain

about the ending being a little too neat --- "nothing works out that

cleanly in the real world, does it?" -- are missing the point: the

tying up of every single loose end into a nice little bow is exactly

what elevates the film into greatness.

A second distinction

between "Lock, Stock.." and the average genre film lies in the inherent

intelligence of the characters. There isn't

a single moment where a character indulges in stupidity in the service

of plot complications --- no gloating villains who inexplicably fail to

gun down the brave hero at the earliest opportunity. When characters

find their fortunes swaying, the fault lies not in themselves but in

their stars, thus leaving intact the internal plot logic and making the plot's

use of such vicissitudes of fortune far more acceptable than would

otherwise have been the case.

At

the end of it all, watching "Lock, Stock.." is

probably not going to

teach anyone anything more about humanity than they already knew. But

it sure is a whole lot of fun sitting through it, and picking up such

perfectly utilitarian skills as being able to speak Cockney

slang. Still don't Adam a dickie of all this

rabbit?

Take a butcher's yourself.

Cockney Rhyming Slang

[ Show

|

Hide ]

The

following is a transcription of the Cockney guide that is part of the

DVD release of "Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels".

Forged in Victorian England by

the working-class laborers, and

appropriated by the underworld, Cockney Rhyming Slang is ideal for

those who wish to talk amongst themselves: secret societies,

brotherhoods, gangs and the like. Suppose you're a Rob Roy in a

read-and-write over River Ouse...

All

right, let's translate: Rob Roy=boy, Read-and-write=fight, River

Ouse=booze. So, suppose you're a boy in a fight over booze. When

telling the story

to another lad who's up on his Cockney Rhyming Slang, you can

communicate that much quicker (and more in secret) by doing what the

natives do: dropping the rhyme portion of the phrase.

Therefore: Adam and Eve it or

not, becomes: Adam it or not.

Still scratching your loaf?

Don't you think this makes eighteen? Then

take a butcher's hook at the following study guide.

English

|

Cockney

|

Believe

|

Adam

(and Eve)

|

Book

|

Jackdaw

(and rook)

|

Booze

|

River

Ouse

|

Boy

|

Rob

Roy

|

Church

|

Left

(in the lurch)

|

Clock

|

Dickory

(dock)

|

Cop

|

John

Hop

|

Copper

|

Grasshopper

|

Crook

|

Joe

Rook

|

Deaf

|

Mutt

(and Jeff)

|

Drunk

|

Elephant's

(trunk)

|

Ear

|

King

Lear

|

Ears

|

Sighs

(and tears)

|

Easy

|

Lemon

Squeezy

|

Eyes

|

Mince

(pies)

|

Face

|

Boat

(race)

|

Feet

|

Plates

(of meat)

|

Fight

|

Read

(and write)

|

Geezer

|

Lemon

(squeezer)

|

Girl

|

Twist

(and twirl)

|

Gloves

|

Turtle

(doves)

|

Hair

|

Barnet

(flair)

|

Hat

|

Tit

(for tat)

|

Head

|

Loaf

(of bread)

|

House

|

Cat

(and mouse)

|

Judge

|

Inky

(smudge)

|

Kiss

|

Heavenly

(bliss)

|

Later

|

Alligator

|

Look

|

Butcher's

(hook)

|

Mate

|

China

(plate)

|

Money

|

Bees

(and honey)

|

Morning

|

Day's

(a-dawning)

|

Nose

|

Ruby

(rose)

|

Phone

|

Trombone

|

Pint

(of ale)

|

Ship

(in full sail)

|

Sense

|

Eighteen

(pence)

|

Sleep

|

Bo-Peep

|

Soap

|

Cape

(of Good Hope)

|

Voice

|

Rolls

(Royce)

|

Water

|

Fisherman's

(daughter)

|

Wife

|

Trouble

(and strife)

|

Chevy

Chase

|

Face

|

John

Cleese

|

Cheese

|

Doris

Day

|

Gay

|

Bouter-Boutros

Gali

|

"Charlie"

(cocaine)

|

Lillian

Gish

|

Fish

|

Buster

Keaton

|

Meeting

|

John

Major

|

Wager

|

Mickey

Mouse

|

Scouse

|

Gregory

Peck

|

Neck

|

Christian

Slater

|

Later

|

Donald

Trump

|

Dump

|

Mae

West

|

Best

|

Barry

White

|

"Shite"

|

Additional Resources

More Like This

- Snatch -- Guy Ritchie's fllow-up to Lock, Stock.. is not as good but very funny nevertheless.

- Bound -- The Wachowski brothers' first effort (superior to their subsequent The Matrix) demonstrates a clockwork-precision plot somewhat reminiscent of Lock, Stock....

- The Usual Suspects -- A labyrinthine story told with great flair in a non-linear fashion.

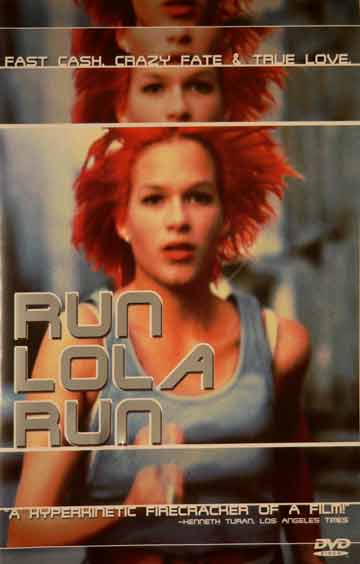

Run Lola Run

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

-- T.S.Eliot, Little Gidding

Every time I watch Run Lola Run, I inevitably find myself comparing it to the O. Henry short story Roads of Destiny . "Roads of Destiny" tracks the fate of a young shepherd called David (no relation to this guy) who decides one day to leave behind his sheep and make his career in poetry. He sets out for the city and promptly loses his way, arriving at the intersection of two major roads with nary a clue as to what direction to take. O. Henry uses this device to tell three different tales of what would have happened had David gone down each of three different paths. While it would be sinful to give away too much more, it is not much of a spoiler to state that the story is an ode to determinacy; O. Henry wants to establish the inevitability of destiny, as David is magnetically pulled towards exactly the same fate in each of the three scenarios.

Tom Tykwer's "Run Lola Run" has a remarkably similar conceit. Lola needs to get a-hold of 100,000 marks (the movie pre-dates the Euro by a couple of years) in 20 minutes in order to save her boyfriend, Manni, from near-certain death at the hands of the bad guys. What we receive is three alternative versions of those 20 minutes, event sequences starting out identically but diverging quickly into three different realities on the basis of Lola's trifling encounter with a dog on a stair.

However, this is where all resemblances, coincidental or otherwise, between O. Henry and Tom Tykwer end. While O. Henry is interested in demonstrating the convergence of alternative realities to the same eventual fate, Tykwer is studying the exact opposite -- the exponentially fast divergence of realities from near-identical initial states. O. Henry paints a world ruled by implacable classical determinism, unswayed by the idle efforts of human free will to distract it from its predetermined destination; Tykwer, on the other hand, thrives in a post-modern, chaotic universe swayed mightily by every flap of a butterfly's wings, held at ransom by the influential repercussions of the apparently inconsequential.

As exciting as all this thematic structure may be, the real strength of "Run Lola Run" as a movie lies in the inventiveness of its storytelling. As Roger Ebert eloquently puts it, Tom Tykwer ``throws every trick in the book at us, then the book, and then himself''. The film is a visual marvel, right from its magnificent opening scene with an aerial shot of a crowd forming the movie title, to its clever use of film stock to separate the main characters from the rest, and interleaved photo montages of tens of pictures that are , naturally, worth tens of thousands of words. Oh, and if that is not enough, there are also freeze frames, jump cuts indebted to 2001: A Space Odyssey , and even some animation thrown into the ring.

The techno soundtrack of the film is a perfect complement to the explosive energy of the visuals. Tom Tykwer, who is also a pretty accomplished musician, composes much of the music for the film, and has even contributed a song to one of the Matrix sequels. (The song is better than the sequel, although that isn't saying much.) Franka Potente, who, as you might have guessed, spends a lot of time running through Berlin streets with flaming hair bobbing all over the place, did manage to retain enough of her breath to provide the vocals for the song accompanying most of her athletic pursuits.

"Run Lola Run" is a smart movie that demands active and attentive watching in order to piece together all the subtle causal connections among various events. I suspect it likes to think that it poses deeper existential questions worthy of greater thought, steeped as the beginning segment is in rhetoric and T. S. Eliot. Personally, I never quite figured out why the Eliot quote had that much to do with the rest of the movie. Not that it affected my enjoyment of it in any way. As they say, the ball is round, and the movie lasts 81 minutes. Anything else is merely hypothetical.

Additional References

More Like This

- The Princess and the Warrior -- Far more subdued sequel from Tykwer, once again starring Franka Potente. Beautiful camera work, although the slow pace is not for everyone.

- Groundhog Day -- Bill Murray is caught in a different kind of time warp, having to live through the same day over and over again.

- Magnolia -- Paul Thomas Anderson's wildly energetic operatic story of coincidences and interlinking lives.

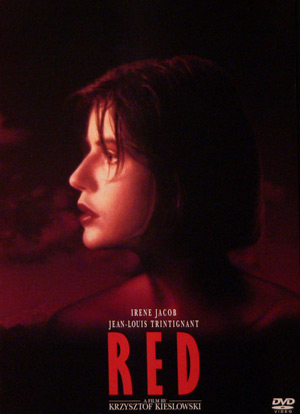

Three Colors: Red

Of all the directors who have garnered universal critical acclaim over the last twenty years, there is probably no one more revered than Krzysztof Kieslowski. Best known for his Decalogue cycle -- a set of ten short films dramatizing the Ten Commandments -- and the Three Colors trilogy, Kieslowski brings a unique filmmaking style to his stories, filling them with subtlety and understatement, requiring rigorous intellectual exercise on the part of the audience in order to understand the filmmaker's intentions. Consequently, sitting through a Kieslowski film can sometimes feel like a daunting exercise; the film's ending does not provide closure in itself, and instead requires us to ponder the events for ourselves to make sense of them.

Three Colors: Red is probably the most accessible of Kieslowski's works and, as such, provides the most painless route into the "I've seen a Kieslowski movie" club. "Red" is the final segment of the Three Colors trilogy, the titles being a reference to the colors of the French national flag -- blue, white and red -- that stand for the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity respectively. Understanding what "Blue" has got to do with liberty, or "White" with equality, turns out to an exercise in itself; luckily, things are a lot more clear-cut in "Red" and it is easy enough to play "Spot the Fraternity" with the story.

Despite all the apparent nods in the direction of fraternity, "Red" is very much a film about chance and randomness. Kieslowski's point is both simple and profound: most events in our lives have an extremely low a priori likelihood of unfolding in the exact way that they do. For example, the chances that two particular, completely unrelated people bump into each other while walking down a street may be extremely small; nevertheless, many pairs of random people bump into each other every single day. And those random bumps can sometimes have dramatic effects on the future course of their lives.

While "Run Lola Run" takes the random-bump concept literally, and runs with it to the logical extreme, Kieslowski is interested not in the consequences of all this randomness (or chaos, if you will) but in its antecedents. Not for him the cheap thrills resulting from the uncertainty of the future. His interest is in following the separate lives of characters who haven't met, wondering about the effects of a meeting on their lives, imagining what might have been had nature played its cards slightly differently, and extracting suspense from the question of whether, and how, their lives will cross each other.

The story of "Red" revolves around a young student-model named Valentine (played by the beautiful Irene Jacob) who accidentally runs over a dog, resulting in a run-in with a retired judge, leading to, you guessed it, a fraternal relationship. The judge happens to be snooping on his neighbors, and gets caught, which brings together many of the people in his neighborhood creating a primordial soup for the establishment of all kinds of relationships. But there are even more layers under the hood, as hidden, unexplained connections start revealing themselves, linking the judge with a young law student named Auguste who happens to be Valentine's neighbor. It is somwhat pointless to reveal any more about the story, since it is as much about what does not happen as it is about what does.

There is a great deal of mirroring and repetition that is in evidence throughout the film, as the same visual patterns arise over and over again in different situations. Part of it is simply film grammar with the filmmaker trying to instill in the audience a sense of deja vu. But Kieslowski also seems to be postulating a deeper statement about patterns repeating themselves in unexplained ways in the fabric of life. One particularly memorable pattern is Valentine's profile (see poster), which happens to adorn a giant billboard in the movie, and then crops up completely unexpectedly in a surprising context. In the chaotic dynamics of life, these patterns, Kieslowski seems to be saying, form the strange attractors of fate.

When I first saw "Red", I knew I had seen a great movie but could think of no rationalization for why I liked it so much. After all, what right did a story about a bunch of random people, meandering through random, and occasionally fantastic, events, have to be this engrossing? I then turned to the ever-eloquent Roger Ebert for his take, hoping to discover the secrets of the film's hidden greatness. But even Ebert, usually highly articulate in his film analysis, was of no help this time, as he was content to outline his emotional reaction to the film, concluding, "This is the kind of film that makes you feel intensely alive while you're watching it, and sends you out into the streets afterwards eager to talk deeply and urgently, to the person you are with. Whoever that happens to be."

I have since learnt a thing or two about the film techniques of Kieslowski -- techniques subliminally impacting the viewer with clever foreshadowing, repetition, and motifs -- but I am no closer to understanding my liking for "Red" than I was when I first saw it. Perhaps it has to do with the technique, or because I find myself empathizing with the characters, or because of its universal themes. All I know is that I belong to the "I've not only seen a Kieslowski movie but I also loved it" club!

Additional Resources

More Like This

- White and Blue -- The other two parts of the Three Colors trilogy.

- Intacto -- Spanish thriller about intertwining fates and a law of conservation of luck.

Chance and Chaos: The

Math and Science

- How

random is a coin toss?

If you were to "vigorously" toss a coin and catch it in mid-air, what

are the chances that it lands heads? Persi Diaconis provides some

surprising results. (You can find a more mathematical treatment here.)

- Does

God play dice?

Stephen Hawking explains that Quantum Theory does not merely state that the future is unpredictable due to the infeasibility of accurate measurements. The fundamental randomness of Quantum physics

dictates that we cannot predict the future even if we knew the exact current state of the universe! So, he claims, God is constantly playing dice to chart the future of the universe.

- A

Random Walk in Arithmetic

Gregory Chaitin explains how randomness crops up surprisingly in number

theory, through a detour into Turing machines and Diophantine

equations.

- An

Experiment with Mathematics

Franco Vivaldi illustrates the emergence of Chaos from the simplest of

equations.

- "Does God Play Dice?: The New Mathematics of Chaos", Ian Stewart, Blackwell Publishers, 2002. An excellent primer on Chaos with tons of beautiful illustrations and the rudiments of a theory that I love: God does not play dice. Stewart explains that the traditional argument for God playing dice has a hole in it - a hole that Chaos Theory can drive through.